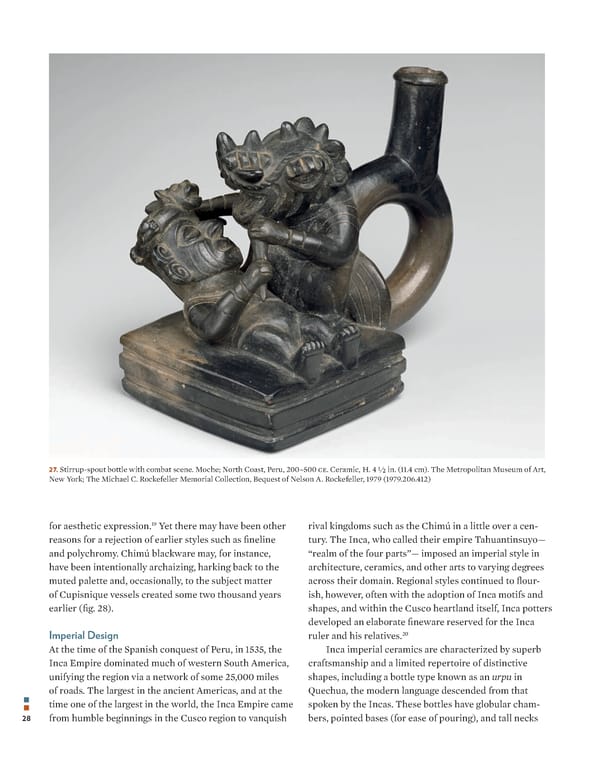

27. Stirrup-spout bottle with combat scene. Moche; North Coast, Peru, 200–500 ce. Ceramic, H. 4 ⼀挀 in. (11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.412) 19 for aesthetic expression. Yet there may have been other rival kingdoms such as the Chimú in a little over a cen- reasons for a rejection of earlier styles such as 昀椀neline tury. The Inca, who called their empire Tahuantinsuyo— and polychromy. Chimú blackware may, for instance, “realm of the four parts”— imposed an imperial style in have been intentionally archaizing, harking back to the architecture, ceramics, and other arts to varying degrees muted palette and, occasionally, to the subject matter across their domain. Regional styles continued to 昀氀our- of Cupisnique vessels created some two thousand years ish, however, often with the adoption of Inca motifs and earlier (昀椀g. 28). shapes, and within the Cusco heartland itself, Inca potters developed an elaborate 昀椀neware reserved for the Inca 20 Imperial Design ruler and his relatives. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, in 1535, the Inca imperial ceramics are characterized by superb Inca Empire dominated much of western South America, craftsmanship and a limited repertoire of distinctive unifying the region via a network of some 25,000 miles shapes, including a bottle type known as an urpu in of roads. The largest in the ancient Americas, and at the Quechua, the modern language descended from that time one of the largest in the world, the Inca Empire came spoken by the Incas. These bottles have globular cham- 28 from humble beginnings in the Cusco region to vanquish bers, pointed bases (for ease of pouring), and tall necks

Containing the Divine | Ancient Peruvian Pots Page 29 Page 31

Containing the Divine | Ancient Peruvian Pots Page 29 Page 31