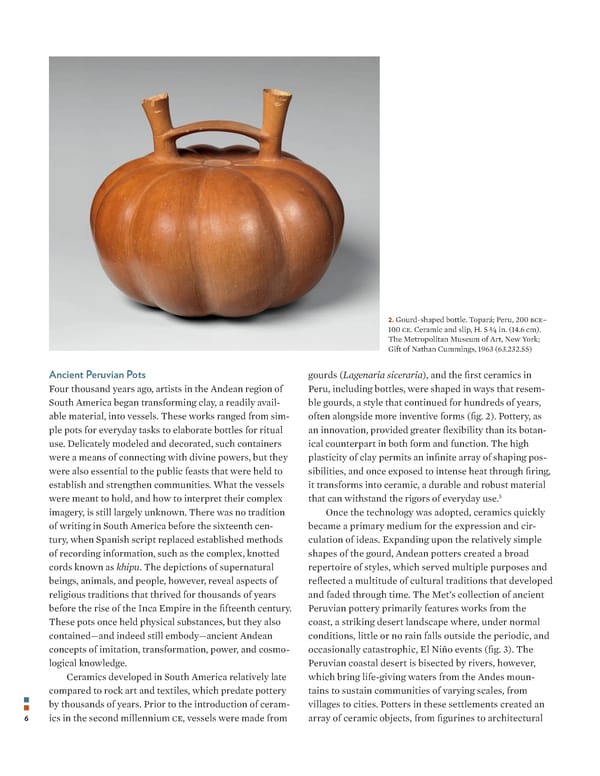

2. Gourd-shaped bottle. Topará; Peru, 200 bce– 100 ce. Ceramic and slip, H. 5 ⼀最 in. (14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Nathan Cummings, 1963 (63.232.55) Ancient Peruvian Pots gourds (Lagenaria siceraria), and the 昀椀rst ceramics in Four thousand years ago, artists in the Andean region of Peru, including bottles, were shaped in ways that resem- South America began transforming clay, a readily avail- ble gourds, a style that continued for hundreds of years, able material, into vessels. These works ranged from sim- often alongside more inventive forms (昀椀g. 2). Pottery, as ple pots for everyday tasks to elaborate bottles for ritual an innovation, provided greater 昀氀exibility than its botan- use. Delicately modeled and decorated, such containers ical counterpart in both form and function. The high were a means of connecting with divine powers, but they plasticity of clay permits an in昀椀nite array of shaping pos- were also essential to the public feasts that were held to sibilities, and once exposed to intense heat through 昀椀ring, establish and strengthen communities. What the vessels it transforms into ceramic, a durable and robust material were meant to hold, and how to interpret their complex that can withstand the rigors of everyday use.5 imagery, is still largely unknown. There was no tradition Once the technology was adopted, ceramics quickly of writing in South America before the sixteenth cen- became a primary medium for the expression and cir- tury, when Spanish script replaced established methods culation of ideas. Expanding upon the relatively simple of recording information, such as the complex, knotted shapes of the gourd, Andean potters created a broad cords known as khipu. The depictions of supernatural repertoire of styles, which served multiple purposes and beings, animals, and people, however, reveal aspects of re昀氀ected a multitude of cultural traditions that developed religious traditions that thrived for thousands of years and faded through time. The Met’s collection of ancient before the rise of the Inca Empire in the 昀椀fteenth century. Peruvian pottery primarily features works from the These pots once held physical substances, but they also coast, a striking desert landscape where, under normal contained—and indeed still embody—ancient Andean conditions, little or no rain falls outside the periodic, and concepts of imitation, transformation, power, and cosmo- occasionally catastrophic, El Niño events (昀椀g. 3). The logical knowledge. Peruvian coastal desert is bisected by rivers, however, Ceramics developed in South America relatively late which bring life-giving waters from the Andes moun- compared to rock art and textiles, which predate pottery tains to sustain communities of varying scales, from by thousands of years. Prior to the introduction of ceram- villages to cities. Potters in these settlements created an 6 ics in the second millennium ce, vessels were made from array of ceramic objects, from 昀椀gurines to architectural

Containing the Divine | Ancient Peruvian Pots Page 7 Page 9

Containing the Divine | Ancient Peruvian Pots Page 7 Page 9